Skill decay among cabin crew is unsettling, insidious and dangerous

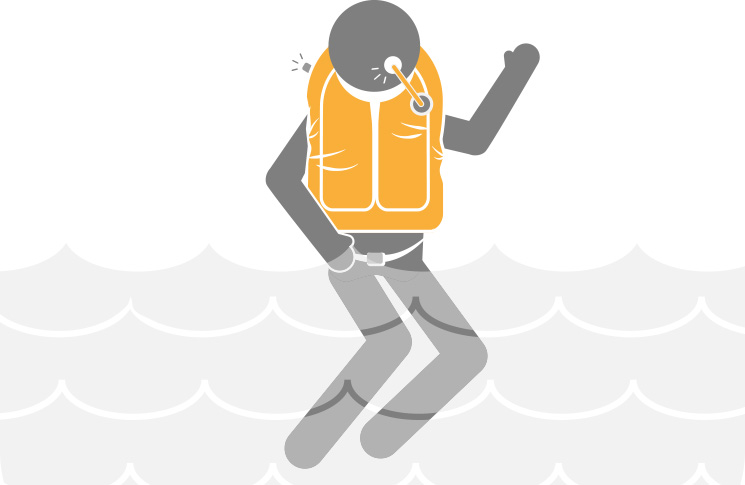

A widely known and deliciously rude description of the role of cabin crew says the essence of the job is saving certain portion of each passenger’s anatomy, not kissing it. The overarching priority for all cabin crew members is safety and their primary function is control and evacuation of the passenger cabin in emergencies. Serving meals and pouring drinks is what they do when not preoccupied by this higher duty.

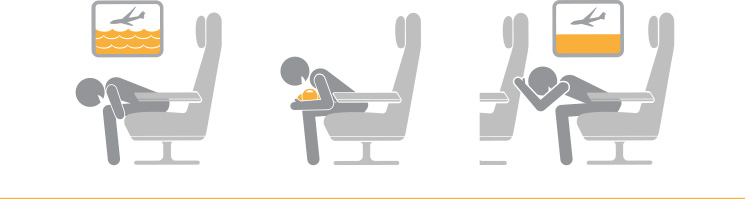

This is a fundamental difference between cabin crew and flight crew. For the men and women on the flight deck, emergency procedures are a variation and extension of what they do every day in flying the aircraft. For cabin crew, they are an entirely different set of skills. From a training point of view, keeping such rarely used skills fresh is a substantial, if largely hidden, problem.

CASA cabin safety specialist, Angela Andrews, says the regulations require cabin crew to be competent at emergency procedures. ‘But what does that mean?’ she says. ‘Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of yardsticks to measure what competence means. It’s not like the flight deck where hand flying can be practised. There’s no similar opportunity in the cabin, no dress rehearsal.’

Cabin crew in Australia must undergo training every 12 months as mandated under Civil Aviation Order 20.11(12). This ensures minimum level of competence in emergency procedures. However, academic evidence that skill decay occurs over much shorter times, is mounting.

In 2006, Stacey Hendrickson and colleagues, from the University of New Mexico, evaluated flight crews six and 12 months after training. ‘Both normal and emergency flight manoeuvers experienced significantly higher decay at the 12-month assessment when compared to the six-month assessment,’ she and her colleagues found. However they noted that pilots who were forewarned and had the chance to mentally rehearse their actions did better.

‘The greater decay suffered by the first-look manoeuvers suggests engaging in mental rehearsal before on-the-line flying might mitigate the decay,’ Hendrickson and colleagues wrote, but concluded, ‘The results, furthermore, suggest the importance of upholding a six-month training schedule.’

A 2008 study by Paul H. Mahony and colleagues investigated the retention of CPR, first-aid knowledge and perceived levels of confidence among 35 cabin crew 12 months after recurrent training. In a mock resuscitation exercise, 33 of the 35 cabin crew failed to use the bag mask correctly, 18 performed chest compressions at the incorrect site, only 13 achieved the correct compression depth and only 20 placed the defibrillator pads correctly.

‘The results of this study indicate that cabin crew may not have sufficiently high levels of skill to manage a cardiac arrest adequately,’ Mahony says. ‘This suggests that existing approaches to training of cabin crew require further investigation and modification.’

KNOWING AND DOING, the essence of skill

The difference between knowledge and skill has vexed philosophers for thousands of years—Aristotle and Plato both mentioned it. In a 2014 paper, philosophy professor Will Small said, ‘the transmission of skill proper appears to resist being treated as a straightforward case of testimony’. In lay language, what he means is there are some things you just can’t learn from a book, or from being spoken to.

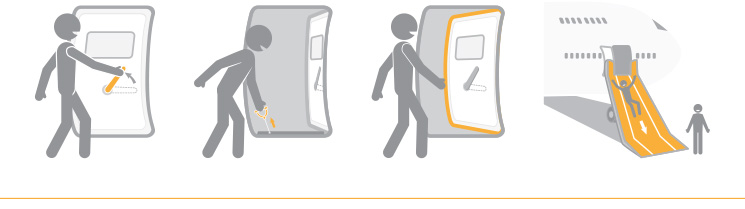

CASA cabin safety inspector Lisa Anseline says cabin crew safety skills have to be taught to a very high, habitual level of competence, which requires more than classroom learning. ‘It’s not that these tasks are particularly complex but they will be vital—your performance will be measured in seconds,’ she says.

Under extreme stress, minor details will become major, such as the subtle differences in cabin door mechanisms on different aircraft types. ‘In that one moment you could mess it up through habit—it’s like when you drive a European car and put the wipers on instead of the indicator. You need a high level of familiarity to avoid that. And while it’s usually no big deal in the car, in a cabin emergency every second counts. You only get one chance.’

Andrews says knowledge and skill are totally different. ‘I could 100 per cent tell you how to follow an emergency procedure, but doing it would be another matter. It requires a different level of familiarity.’

Part of the cabin safety preparedness problem has been the sheer safety of air transport. There has been no fatal crash of a passenger aircraft with cabin crew in Australia since the last day of 1968 when MacRobertson Miller Airlines flight 1750 broke up near Port Hedland, killing all 26 on board. (Australia’s last fatal regular public transport aircraft crash was that of a Fairchild Metro near Lockhart River, Queensland, in May 2005, that killed all 15 people on board.) There was, however, a none-too-orderly precautionary disembarkation via escape slides after Qantas flight 1 overran the runway at Bangkok on 23 September 1999.

Andrews says the background conditions surrounding suspected cabin crew skill decay are an almost textbook case of the preconditions for practical drift, the documented phenomenon where the actual performance of a safety system moves away from its ideal or designed performance. ‘In particular, drift happens when past success is taken as a guarantee of future safety—this can be a downside of a reliance on reported occurrences as the only safety motivator. If there are no reports then there is no reason for concern.’

In 2016, researcher Zakariah Bani-Salameh found ‘lack of preparedness and decay of expertise among flight attendants.’ He recommended ‘that frequent brief skill reviews be used through educational technologies to improve retention of skills and this can be done before pre-flight briefing, and the frequency of a refresher course should be less than 12 calendar months.’ Bani-Salameh described his findings as ‘calls for help by the flight attendants and they should be attended to immediately’.

Bani-Salameh found a link between exposure to real life emergencies and proficiency in emergency procedures. ‘An interesting finding of this study was that flight attendants who experienced on-board emergencies and successfully solved the emergency situations improved their perceptions of the usefulness of the safety manual, the importance of pre-flight briefing, and continuous mental practice and rehearsal. These findings showed that among flight attendants, experience was the best teacher.’

From this he draws the lesson that realistic simulation could, and should, usefully mimic the intensity of these experiences. ‘Real-life experiences are similar to simulations provided by the use of multimedia and educational technologies which are not used in training,’ he argues.

‘This is a very expensive and risky way maintaining expertise,’ he concludes drily.

Further information

Bani-Salameh, Z., Abbas, M., & Bani-Salameh, L. (2010). Optimizing flight attendants’ retention of safety knowledge and skills can enhance crew resource management. Flight Safety Foundation: AeroSafety World, July 2010, pp. 44–47.

Bani-Salameh, Z. (2016). Perceptions of Safety Knowledge and Skills in Vocational Training. International Education Studies, 9(5), 133.

Hendrickson, S. M., Goldsmith, T. E., & Johnson, P. J. (2006). Retention of Airline Pilots’ Knowledge and Skill. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 50th Annual Meeting pp. 1973–1976. SAGE Publications, Los Angeles, CA.

Small, W. (2014). The transmission of skill. Philosophical Topics, 42(1), pp. 85–111.

Comments are closed.