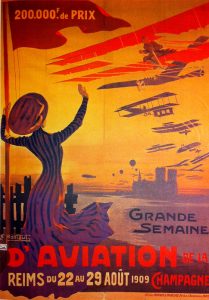

Airshows have been part of aviation since 1909, when 500,000 people turned out to see the Grand Week of Aviation, at Reims, France. They are powered flight’s last link with its barnstorming origins, when pioneer aviators would fly from town to town performing hair-raising stunts and offering rides to the courageous.

Historian, David Onkst, wrote that barnstorming ‘seemed to be founded on bravado, with “one-upmanship” a major incentive’. In its early 20th century heyday, it was conducted under no regulation whatsoever, and had a correspondingly high rate of accidents and deaths. Onkst cites a figure that up to 90 per cent of the exhibition pilots of the early barnstorming era died while flying.

Modern airshows have evolved into big business. Australia’s major airshow, the biennial Australian International Airshow, at Avalon, in Victoria, is reckoned to generate the equivalent of 2000 full-year jobs and a gross economic benefit of $146.2 million. Britain’s Farnborough airshow boosted the UK economy by £57.4 million ($A95 million) and the 300 air shows every year in the US are estimated to have a direct economic impact of more than $A400 million.

Whether trade fairs or enthusiasts’ gatherings, airshows have the task of tipping their hat to the barnstorming days while maintaining the safety expected of modern aviation.

They have to manage not only the usual risks of flight, but also the additional risks of low-altitude flight, formation flight, aerobatics, pyrotechnics and huge crowds.

This doesn’t always work out, as the crash of a Hawker Hunter at Shoreham in England in 2015 sadly showed. The vintage jet failed to pull out of a low-level loop and crashed on a road near the airfield, killing 11 unofficial spectators and passers-by. (See Untidy wreckage: the aftermath of Shoreham Airshow crash.)

After the shock of Shoreham, the British Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) calculated that in the UK there had been one fatal accident per 2960 display items in the period 2008 to 2015. The International Council of Air Shows (ICAS), the flying display industry body in the US and Canada, estimated that in the USA the civil air display accident rate was one fatal accident per 5600 display items. This rate is several orders of magnitude more dangerous than scheduled airline flying, which had one fatal accident for every 29 million flights in 2015. Yet, safety of a kind is ensured by prioritising the safety of the general public, airshow spectators and display pilots—in that order.

Worldwide, airshow crashes kill individual display pilots at the rate of several every year. But airshow accidents that kill multiple spectators or crew occur, on average about once every decade. However, as in airline transport, Australia has enjoyed a better than average safety record, although in a largely forgotten crash, six pilots were killed in 1962 when four RAAF de Havilland Vampires hit the ground during formation aerobatics practice. There have also been crashes at Parafield in 2013, Nowra in 1999 and Mt Gambier in 1998, that killed display pilots, but no spectator deaths.

Airshow display safety is managed by putting it in a box. The display box is an invisible, but inviolate space in the sky where the display aircraft must remain throughout its manoeuvres. There are two conceptual boxes—one in which the aircraft must perform, and a second, larger space that varies by aircraft speed and type. It has to be large enough to contain any accident that does happen without additional casualties on the ground.

Avalon Airshow display organiser, Glyn Butchard, explains, ‘There are a series of lines that run parallel to the crowd line; they run out 100, 250, 350 and 500 metres. These lines are set up so that based on an aircraft’s weight and speed, and hence its turning radius and momentum, if something was to happen to an aircraft, say control surface failure, then the aircraft should fall short of the crowd line.’

Avalon’s line placement is ‘over and above the requirements laid down by CASA’, Butchard says.

CASA certificate team manager, safety assurance, John Costa, says, ‘We’re very strict on that when it comes to displays. There needs to be a certain distance where, if there is an incident, the debris that comes off the aircraft will not impact people. That varies by aircraft type and performance.

‘We look at the appropriateness of the aerodrome for the display. For Avalon that’s not usually an issue, although it’s complicated by having pyrotechnics operating in the aerodrome area. It’s fairly straightforward because there’s plenty of open space and that allows for good safety margins.’

‘We have to consider safety of people nearby—including unpaid spectators. For example, at the Tyabb Airshow, the general public walk behind the display runway.

‘There’s also general crowd control, particularly for smoking round aircraft and fuel. We monitor crowds as well as the display.’

Display pilots: send home the clowns

CASA takes display pilot licensing and selection very seriously and requires airshow organisers to do likewise. ‘For every pilot in a display we make sure they are approved, they are current, they are endorsed, and that they have a current medical,’ Costa says. ‘That takes up the majority of our time. Then we make sure the aircraft is certified.’

Temora Aviation Museum general manager, Peter Harper, says pilot selection is central to running a safe air display. ‘We’re keen to get a flow of new pilots, but we’re also very selective. You don’t get a guernsey just because you have thousands of hours in a 747, for example,’ he says.

‘The museum looks for relevant experience, attitude and skill, all of which it considers equally important.

‘First and foremost they have to have hours, and they have to have an internalised safety culture. We really quiz them hard about their systematic approach to safety.’

CASA flying operations inspector and airshow display pilot, Derek Fox, says flying even a short display requires committing a great deal to memory in the name of safe coordination with other displays. ‘All display pilots must know the act before them and the act after them. I’ll be flying at Avalon myself and I already know who I’m following and who’s following me.’

‘We’re required to keep our eyes and ears wide open to what’s going on. Any pilot who doesn’t attend the daily brief is not allowed to fly.

‘We also have to consider the RPT operations into that aerodrome. That’s mapped out weeks before but has to be confirmed on the day.’

Harper says Temora, as a small flying display, has the luxury of insisting timing comes second to safety. ‘As far as we’re concerned, there should never be any hurry. Although we assign times to each aircraft, they are indicative only. We don’t want anything being rushed into error.’

Organisation: three rings under the big top

‘We have 21 air displays a year, weather permitting,’ Temora Aviation Museum chief executive, Murray Kear, says. ‘Our advantages are motivated personnel, but also the organisational structure of the museum, which was deliberately set up to create redundancy, clear lines of responsibility and to separate commercial from operational pressures.

‘The overall organisation consists of three sub-branches. There’s Temora Aviation Museum, a commercial and education entity,’ Kear says. ‘It is separate from Temora Historic Flight Club, which runs the operational and flight line processes, including safety briefings.

‘We attend those briefings, but the whole operation moves over to them on air showcase day. It’s a transfer of responsibility that alleviates potential commercial pressures. They have unlimited call on what flies or doesn’t fly.’

The engineering side is set up as another separate entity: Temora Aviation Museum Engineering. ‘The experience is you create separate governed entities that have the call on what’s done in their field of business, and that enhances safety,’ Kear says. ‘You don’t have the cross-pollination of having the commercial pressure to do something and it also avoids one side becoming dominant. It’s like a three-legged stool.’

The various organisations cross-check each other, in areas such as pilot and maintenance currency. ‘I’m a pilot myself and I’m aware of how your medical, for example, can creep up on you,’ says Kear. ‘They in turn ask us about our emergency response.’

Cracking the whip: the ringmaster

Fox says one of the most important choices for a safely run airshow is selecting the right person to act as display coordinator, or ‘ringmaster’. ‘They are the ones who run the whole show—their team has to be very experienced.’

A ringmaster has to combine managerial talents with aeronautical experience and judgement, and overlay these with authority. People with the combination of skills to assess the safety of an air display and issue a ‘knock-it-off’ order if the display exceeds safety parameters are rare, and valued.

Butchard describes the ringmaster’s role as, ‘scheduling, choreography and facilitation of what the public sees; the integration of all the acts into a seamless flying display. The ringmaster is responsible for oversight, qualifications, safety assessments and ultimately guiding ATC to facilitate the flying display,’ he says.

‘There are a number of aircraft flying at any one time; display aircraft, aircraft in holds, and aircraft on the ground.

The ringmaster is like a conductor of an orchestra, bringing all these aircraft in at the right time.

‘All going well, the ringmaster won’t have to do much, but must be able to step in as required if display schedules slip, or there’s an inbound aircraft.’

The ringmaster’s airshow day starts early, with the morning’s display brief. ‘The display coordinator meets every morning with show organisers to look at risks identified during that day,’ Costa says. ‘They combine daily knowledge, experience and judgement. The buck stops with them.’

Butchard says Avalon has a flying control committee that oversees both the ringmaster and the flying display participants. ‘If there is a breach of the regulations we can debrief the participants or the ringmaster and make sure we address the issues that come up at the time,’ he says.

A foreign field: the legacy of Shoreham

The Shoreham crash was an unpleasant reminder of the risks inherent in display flying and the need to manage them actively. ‘It was an opportunity to look more closely at what we were doing,’ Costa says.

‘After the Shoreham accident, CASA gathered inspectors from each office. We met in Adelaide and went through the current display manual and the Shoreham report, and looked at all the recommendations in that document. We compared them with what we actually did.

‘As a result we’ve almost entirely rewritten the display manual and we’ve incorporated all the Shoreham recommendations where we can, where they affect Australian legislation, and how we do our displays.

‘We incorporated every one of the AAIB’s Shoreham recommendations into the new manual,’ he says. ‘In fact there were only a few of them that we didn’t already have in place. But they have been made clearer in the new manual.’

One particular hypothetical exercise produced a reassuring result. ‘We held a workshop soon after Shoreham and determined that we would not have issued approval for that particular show because of the population density of the surrounding area,’ Costa says.

Definitions are more explicit in the new manual, due to appear in 2017, Costa says.

The new manual contains standardised coded public address announcements, such as calls for assistance, lost children, and aircraft crashes on and off the field.

The manual also distils decades of CASA and industry experience into a comprehensive safety guide. ‘We now include for the first time a risk assessment process. It’s 20 of the high-risk areas we’ve noted over previous air displays. Risk assessment can capture these risks and reduce them,’ Costa says.

Highwire act: evolving hazards

This year’s Avalon Airshow will introduce a major innovation behind the scenes—civil and military air traffic control will cooperate. Butchard says, ‘Airservices Australia will retain the lead for all air traffic control at Avalon airfield, Avalon east and for the flying displays. Several RAAF liaison officers will be in the tower at the same time.

‘While the RAAF ATC won’t be participating in the physical ATC, they will be observing during the RAAF showcase and displays.’

Speaking as an airshow pilot, Fox says the most significant new risk has been that from improperly flown drones. They were of enough concern for him to adopt a new protocol in a recent display. ‘Flying over Springvale cemetery (near Moorabbin airport) there’s nothing to stop a drone coming up to our level,’ he says. ‘Our mitigator was we all had to have helmets on and visors down, for if a drone hit the windscreen.’

‘In farming communities people have their own drones now, that weren’t stakeholders before—now they are. And we need to communicate with them.’

Butchard says amateur-flown drones will not be allowed within the airshow site, ‘because they do present a safety hazard. We are very conscious of the rise of drones and we’ll be monitoring the situation.’

Costa says airshows generate considerable work for CASA, which takes it on to support the aviation industry. ‘There’s a lot of detail and effort, a huge involvement for us. CASA bears the cost for a huge amount of work that goes on before, during, and after the show.

‘And the process for the next airshow starts the day after the show ends.’

Untidy wreckage: the aftermath of Shoreham Airshow crash

Untidy wreckage: the aftermath of Shoreham Airshow crash

On 22 August 2015, a Hawker Hunter crashed during an air display at the Shoreham Airshow, in southern England, killing 11 people on a road near the airfield. Video shows the aircraft flying a loop and hitting the ground before it could recover level flight.

The UK Air Accident Investigation Branch (AAIB) is yet to issue its final report on the Shoreham crash. However, its special report of 4 September 2015 said the pilot had begun the loop at an altitude of 200 ft—300 ft below the minimum prescribed for standard aerobatic display manoeuvres.

In a report issued in September 2016, the AAIB said the airshow’s flying display director (FDD) did not know what manoeuvres the pilot of the Hawker Hunter jet planned to make.

The AAIB report said, ‘Without prior knowledge of G-BXFI’s (the Hunter’s) display routine or the ground area over which the pilot intended to perform, it was not possible for the FDD to identify the specific associated hazards, where the various aerobatic manoeuvres would be conducted, and therefore to determine which groups of people would be exposed to those hazards and to what extent.’

The September AAIB report described previous non-compliance by the Shoreham Airshow. Video footage of a previous display by the Hawker Hunter at the 2014 Shoreham Airshow indicated that the majority of its aerobatic manoeuvres (including steeply banked turns) had been flown away from the airfield, over areas accessible to the public and outside the control of the display organisers.

‘Footage and tracks determined from radar data showed that the aircraft overflew residential areas along the A259 south of Shoreham Airport several times and in one manoeuvre overflew the central area of the town of Lancing at an angle of bank in excess of 90 degrees,’ the September report says.

‘The pilot was not instructed to stop this display. Either these regulatory infringements were not detected by the display organisers or were not understood.’

The Shoreham investigation parallels a possible criminal prosecution of the pilot, who survived the crash and faces the prospect of being charged with manslaughter by gross negligence. After his release from hospital, he was interviewed by the police in late 2015.

The Police applied to the UK High Court to obtain records of the interviews between the pilot and the AAIB. In keeping with the principles of Annex 13 to the Chicago Convention governing civil aviation, as these are now reflected in the applicable European legislation, the court denied this request. However video footage of the crash, from two cameras on the aircraft, was turned over to police. This footage was found to be for commercial, rather than safety-related, purposes and not subject to the protection afforded by Annex 13 or the European legislation.

However, any attempted prosecution is unlikely before the AAIB issues its final report. A coronial inquest into the crash has also been delayed pending the results of the police investigation. At the time of writing the only thing final to come out of the Shoreham crash is the death of 11 people.

Further information

Selected airshow crashes