A pilot and his passenger are lucky to be alive after their 1942 de Havilland biplane lost its propeller during an aerobatic joy flight in Queensland.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) released its final report into the incident in which the vintage aircraft sustained substantial damage after a forced landing on mud flats near Shute Harbour airfield in July.

With the one passenger on board flying at 3500ft over Pioneer Bay, the pilot began his aerobatic routine, completing the first manoeuvre without incident. But on starting his second move—a loop— the joy flight took a not so joyful turn.

Applying full power and raising the aircraft’s nose, pilot and passenger heard a loud bang, with the pilot noticing a small object fly past his left at close range.

Discontinuing the move, the pilot stabilised the aircraft in a glide and quickly noticed that despite the tachometer indicating maximum RPM, there was no aircraft vibration and the engine wasn’t producing any thrust—regardless of throttle position.

The pilot advised air traffic control (ATC) that they had ‘completed operations’ and were returning to Shute Harbour ALA—at no time stating there was an emergency.

But with no power and diminishing altitude, the pilot realised they weren’t going to reach Shute Harbour and turned towards the beach at Funnel Bay. After seeing boats moored on the shore, the pilot aimed for the mudflats and made a forced landing before continuing onto rocks.

After landing, the pilot inspected the aircraft and realised the propeller was missing.

In the final report released by the ATSB, the pilot indicated that he’d performed visual checks of the propeller for defects, gravel rash, and chips before the flight and had not detected anything abnormal. He assumed the failure was caused by a bird strike.

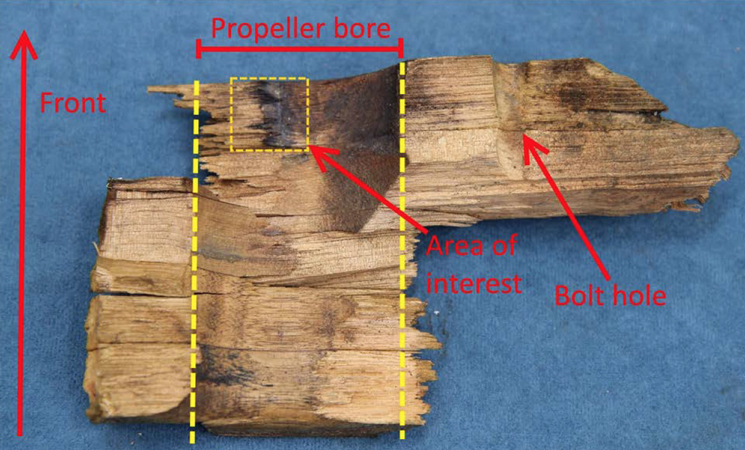

An aircraft maintenance engineer assessed the remaining remnants of the timber propeller left on the aircraft and contacted the manufacturer to trace the part’s history. Although the maker didn’t inspect the remnants, it did suggest the failure was ‘indicative of a propeller over speed.’

The remnants were sent to the ATSB, who concluded there was ‘evidence of bending consistent with the blade breaking away from the hub while under load.’

On board video evidence also suggested that the failure occurred ‘just as the aircraft nose passed back up through the horizon at the start of the next manoeuvre (the loop) and power was applied. The propeller was under substantial load at this stage,’ said the ATSB.

However, because the propeller was not retrieved due to failing over water, the contributing factors to the failure could not be determined based on the available evidence.

No bird remains were found on the remaining remnants.

The incident prompted the ATSB to remind vintage aircraft operators about the limitations of their aircraft:

‘The ATSB cautions commercial vintage aircraft operators about the risks associated with aircraft age and the importance of understanding the originally-intended use of the design before commencing their operations.’

The report also referred to the fatal crash of a de Havilland Tiger Moth in 2013, noting that the in-flight break-up occurred despite the ‘types of aerobatic manoeuvres conducted during the accident flight (all being) permitted for the aircraft type.’

The ATSB complemented the pilot on having a secondary plan to land on the beach at the Funnel Bay, stating the incident ‘highlights the value of always having a consideration of landing areas available in case a forced landing is required.’

However, the crash investigator also asserted that ‘alerting air traffic control as emergencies arise enables them to provide the necessary and appropriate assistance.’

You can read the full report in Issue 54 of the ATSB’s Aviation Short Investigation Bulletin.