A Hawker 700A that crashed into an apartment in the US state of Ohio was airworthy. But the organisation that operated it was broken.

‘We’re completely at a loss for words. We are very confident that they’re a good crew and it’s a very good airplane.’ Augusto Lewkowicz, chief executive, Execuflight Aviation

‘Life you may evade, but Death you shall not.

You shall not deny the Stranger.’

T.S. Eliot, choruses from The Rock

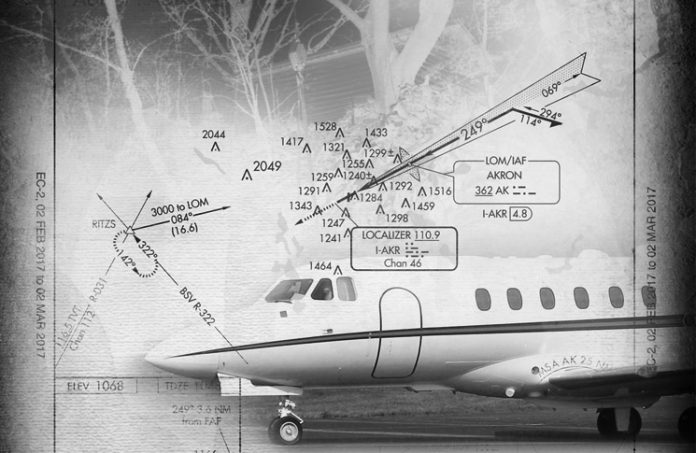

It was 10 November 2015 and the company chief executive was responding to the media. He had lost one of his Hawker 700A corporate jets to an accident just short of the main runway at Akron Fulton in Ohio. The catastrophic impact destroyed a four-unit apartment block, while the seven passengers and two pilots on board were killed by blunt force trauma and inhalation of combustion products. It could have been much worse, but when the Hawker broke cloud base at 400 ft and crashed into the building, all the apartment’s residents were miraculously out for the afternoon. News media had been quick to seek comment from the company and the chief executive had been quick to respond. ‘We are very confident that they’re a good crew and it’s a very good airplane … we are just as shocked as anyone else.’

The statement was made within hours of the accident and the media cleverly juxtaposed the chief executive’s words with security camera images showing the impact fireball. The startling irony in his comments was as glaringly obvious as the gloomy black smoke rising steadily upwards. A good crew flying a good aeroplane? Why then was the burning wreckage of Execuflight 1526 embedded in the side of an urban apartment block?

To be fair, one shouldn’t scrutinise too heavily comments made under the pressure of television cameras. But that was the thing, some six months later, when the National Transport Safety Board (NTSB) released its accident report detailing the numerous organisational failures within the company, the chief executive responded, ‘At the time of the accident, Execuflight had in place a robust safety culture, sent its pilots to an industry-leading training center, had well-proven standard operating procedures (SOPs), and used effective check and balance measures to ensure the above standards were implemented. These were designed, if followed, to prevent an occurrence such as Execuflight 1526.’

The formal response was pretty much the same as the informal one—we’ve got great crews and a ‘robust’ safety culture and we’re not really sure why the accident occurred. The chief executive then went further and suggested NTSB investigators had over-stated key facts and perhaps it ‘would be in the best interest of aviation safety for the NTSB to address the actions of air traffic control as a contributing cause to this accident’.

His comments, as we shall see, focused on the pimples in other organisations rather than the cancer in his own, only accentuating the irony of the original statements. Robust safety culture? Effective checks and balances? Why then such a catastrophic accident?

The damning accident report into the Hawker 700A cited, among many other things, multiple deviations from SOPs, failed supervision, failed training systems and a ‘casual attitude towards compliance’. NTSB board members in the media conference were unequivocal. ‘Protections built into the system were not applied … and they should have been … passengers expect, and should expect, to be flown by well-rested, well-trained, competent professional pilots within applicable regulations.’

They then went on to demonstrate comprehensively that the accident aircraft was actually flown by fatigued, inadequately trained pilots who breached numerous applicable regulations on the back of a legion of systemic failures. An NTSB board member described the company as being ‘infested by sloppiness … from the cockpit to the corporate offices’.

Several lawsuits were soon to follow as was the public testimony of a former captain who alleged the company destroyed and altered records after the crash. He publicly alleged, ‘They made such a scramble to change records and eliminate stuff right after that accident, it would make your head spin. I know they created false weight and balance. I know that for a fact … they were doing everything they could to make sure that they weren’t putting [the] company at fault.’ But according to the company chief executive, ‘Execuflight had in place a robust safety culture … well-proven SOPs … and effective check and balance measures.’

In the 1800s, when fisherman over-stated catch sizes, a new idiom emerged which we know today as a ‘fish story’—an exaggerated story or an improbable, boastful tale. Under the microscopic scan of the NTSB investigation, it become clear the chief executive of Execuflight was greatly exaggerating the condition of his company’s safety culture—he was telling a safety fish story. It was with further irony then, that a month after the NTSB released its report, the Oxford Dictionary released its word of the year: ‘post-truth’. Post-truth describes circumstances, normally political ones, ‘in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’.

In at least three truth-distorting ways, the Execuflight 1526 accident demonstrated post-truth seepage into the unforgiving world of aviation safety. Firstly, in disaffirming objective facts. In the immediate aftermath of the accident, and then again when the investigation was complete, the company chief executive consistently disaffirmed any suggestion the accident pilots were under-checked and under-trained. Instead, he drew attention to the fact the company used accredited simulator training and stated again the accident captain was a competent, well-trained pilot. He further emphasised the fact the captain had, at one point, flown a check ride under the observation of a Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) official without adverse comments. Likewise, there was no concern over the hiring of a copilot with a suspect career history since he was to be employed as second in command. As far as the chief executive was concerned, the company’s ‘robust’ safety culture was keeping everyone safe. But the objective facts of the matter insisted on a different story—the captain and the copilot had both been fired from previous jobs and their background information was never thoroughly checked despite a legislative requirement to do so. If the background check had been done, the company would have known the copilot had been fired because of serious concerns regarding his ability to conduct basic flight sequences.

This systemic failure meant that on the day of the accident, the cockpit voice recorder showed multiple deviations from procedure with the captain constantly having to explain, then re-explain, the basics of the approach to the copilot. At one point, the controls of the aircraft were being so badly mishandled by the copilot that the captain, clearly exasperated, exclaimed, ‘Look you’re going one twenty. You can’t keep decreasing your speed … we’re gonna stall!’ To which the copilot, task-saturated and not noticing the imminence of the stall that would kill them replied, ‘How do you get one twenty?’

The captain dutifully explained the basics of how he’d arrived at an observed airspeed of 120 kt as the aircraft continued its unstable approach. The copilot should have known the speed himself without having it explained and by now, with the aircraft in an unsafe condition, the captain needed to take over. Especially when the captain noticed an extreme rate of descent and exclaimed, ‘You’re diving. You’re diving. Don’t dive. Two thousand feet per minute buddy …’

Assertiveness and leadership, both basic tenets of crew resource management (CRM), would have seen the captain take over and make the decision to fly a missed approach. It was surprising that he had even let the copilot fly such a challenging, down-to-minimas approach in the first place. Then again, perhaps his lack of assertiveness wasn’t that surprising considering the company’s ‘tick and flick’ CRM program which solely comprised a ten-question exam. Investigators found the captain had scored a 40 per cent result but then inexplicably been marked up to the pass rate of 100 per cent. There were many more crew deficiencies which are well reported in local newspaper reporter, Paula Schleis’s story of the accident and is well worth a read. In any case, when the aircraft exited cloud a few miles short of the runway it was already stalled without hope of recovery. Still, even on learning this from the accident report, the chief executive insisted on disaffirming the causal factors with the highly tweetable, post-truth comment, ‘We have a robust safety culture’.

The second post-truth dynamic that could be seen is the delegating of blame and responsibility to other parties, such as the FAA and Air Traffic Control (ATC). In some ways it is understandable that the company would point out that an FAA inspector had observed the pilot on a training flight and had nothing to say. The NTSB also highlighted this fact and observed the FAA’s supervision of low-capacity charter operations was lacking. This fact though was a pimple compared to the cancer-cluster of problems within the company and, as the NTSB correctly pointed out, ‘the operator is the first line of defense against procedural noncompliance by setting a positive safety attitude for pilots’.

This post-truth re-delegation of responsibility went even further when it came to ATC. The chief executive suggested in his formal response that ATC were a ‘probable cause’ in the accident and this should be documented by the NTSB. Again, he was attempting to leverage off an element of truth. ATC, during a heavy workload period and a crew changeover, failed to update the pilots about a slightly lowered ceiling. Regardless of this, the pilots had more than enough weather information from other sources to know the approach was going to be all the way to the minimums. As the NTSB concluded, ‘the air traffic controller’s handling of the flight was not a factor in this accident’.

The third post-truth distortion came in the way the company superficially over-stated its commitment to safety while under-stating its very real deficiencies. To put it another way, the company exaggerated its safety preparedness. This was evident in the chief executive’s submission introduction, ‘Through this submission, we wish to describe some of the rigorous safety protocols that are in place at Execuflight’. And later, ‘Execuflight has a strong safety record and is committed to continuously improving its systems and enhancing its safety culture’.

Six months of investigation, 137 pages of reporting and 29 findings detailing breached SOPs, excessive duty times, failed supervision, failed management, inadequate training and perfunctory human-factors training were completely understated by the chief executive in classic post-truth fashion. While the NTSB asserted ‘Execuflight’s casual attitude towards compliance with standards illustrated a disregard for operational safety’, the chief executive insisted they had ‘rigorous safety protocols’ in place. If only the time and resources spent on embellishing safety had been proportionate to the time and resources spent enacting it.

Execuflight’s safety fish story—its post-truth attempt to disaffirm, delegate and play loose with objective facts, teaches a critical lesson for a post-truth world: aircraft don’t hold together because of pleasing rhetoric and flashy buzz words. There’s really no place for safety fish stories in aviation. Such stories might convince shareholders, board members and casual observers, but they can’t convince physics any more than they could convince a stalled Hawker 700A to climb safety away from a legion of systemic failures. Words are words, actions are actions and actions always outweigh words when it comes to safety. If your company is into ‘post-truth’ and safety fish stories they may be avoiding the consequences of an audit but they will never avoid the consequences of crumpled metal and blunt force trauma.